Catalog, Museum of lower Austria – May 26, 1991

Installation at the Niederösterreichisches Landesmuseum in the Minoritenkirche Krems/Stein

"KINDSKOPF", HELNWEIN'S PLEA FOR A DIFFERENT CHILDHOOD

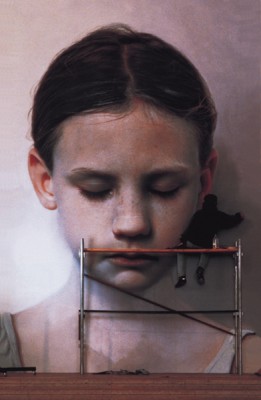

The auratic face of a child, six metres high, four metres wide, hanging in the triumphal arch of a medieval church, surrounded by dozens of canvases in the standard size of 200 by 140 cm that are mounted on the church's pillars and walls show heads and fantasy creatures which only on closer inspection may be easily recognized as children's drawings - once more Helnwein upsets traditional structures of perception in a number of ways, including the expectations that visitors have of a Helnwein exhibition. This is signalled already by the title "KINDSKOPF", which in addition to being a reference to the theme depicted (the head of a child) refers to the ironically serious self-representation of the artist (in German "Kindskopf" is a somewhat condescending colloquialism for an adult acting in childish ways), similar to Helnwein's earlier catalogue title "Subhuman" ("Untermensch") of 1988.

"There is something dark in me, underneath all thinking, that I cannot measure with thoughts, a life that does not express itself in words but that is nevertheless my life..." (Robert Musil, Young Törless)

These words of the young Törless from his speech to his perplexed teachers describe a state of consciousness which is relegated from adult everyday life in the same way that Törless is expelled from the boarding school, the supervisory structures of which can no longer deal with such an insight. What cannot be expressed in word emerges in images, whose formulation the secularized adult society of modern times has left to the artist, who is thus assigned a definite social function. The child on the contrary, asocial in this sense, suffices unto himself, and does not need to appropriate his images; they already belong to him.

That which is underneath all thinking and thus opposed to the reality that can be experienced empirically has for many years now been expressed by Helnwein in images that reflect a "hunger for intensity" (K. A. Schröder, Die ldierte Wirklichkeit, 1987). In his Photo-Realist portraits (or more precisely, portraits painted on the basis of Photo-Realist painting) "this hunger for intensity" takes the form of a desperate striving for the impossible goal of having reality find its complete expression in its image. The price for this is an exaggeration which at times even turns into caricature; in this way the artist achieves what corresponds to his understanding of art as a mass media means of communication: that the work of art is completed only by the viewer's reaction to it (quite intentionally in the sense of a therapeutic recognition of one's own self).

Helnwein's works of art can only be decoded within the framework of his entire concept, in which the misunderstanding of the (pseudo-autonomous) individual work is nevertheless inherent as is a didactic that can very easily be described in the terminology of classical rhetoric: the viewer is entertained and made curious by the choice of a spectacular subject (delectare); he is taught by means of the precise rendering of the individual motifs (docere); and captivated by the suggestive power of the painterly representation (persuadere). However, this suggestive power no longer bases its legitimacy, as it had traditionally done, on the artist's imagination but on the reference to photography which still enjoys the reputation of the authentic even after having been refuted in the mass media reception of its 150th anniversary.

Irritation and shock, i.e. the provocation of an extreme reaction, have been a characteristic of Helnwein's ouevre since his early works around 1970, especially his self-portraits and images of children, whether in the medium of (actionist) photography or a drawing. In these works the shock is not caused by the painstaking narrative treatment of gruesome details or frightening situations - for this has been known to every Central European, above all every Austrian, from the Baroque art of the Counter Reformation which following the rhetoric indicated above used exactly the same means that have been familiar to us for centuries in all their bloody details from thousands of altars. What is shocking is rather the transferral of this concept to a secular everyday "object", and what is more to one that has usually not been consciously perceived. Helnwein's depiction of a child as a stigmatized saviour (Lichtkind/Child of Light, 1972) focuses on the contradiction between a (Christian) ideology that believes in a child as the bringer of salvation - to whom the wise (St. Mathhew 2,11), the old (St. Luke 2, 25 ff.) and prophets (St. Luke 2,36 ff.) bend their knees and pay homage - and the actual standards and practices of society today.

The arrogance, egocentricity and ignorance which children encounter in our society is contrasted with Helnwein's image of the child that completely lacks the concomitant other side of this behaviour: no misguided treating of children as simple-minded creatures, nothing of the happy innocence with which children are cloaked, both in the family album and in advertising, as a projection of an ideological transfiguration of one's own childhood into a grownup reality which is experienced as unsatisfactory (cf. Also Peter Gorsen in the catalogue of the Helnwein exhibition "Subhuman"/ "Untermensch" 1988 and Reinhold Misselbeck in the catalogue of "The Night of Ninth November"/ "Neunter November Nacht" 1990).

Helnwein has summed up his iconology of the child in his monumental photo installation "The Night of Ninth November". Irrespective of the political-historical frame of reference that is indicated by this title, -- "Kristallnacht", night of violence against Jewish persons and property carried out by the German Nazis on November 9-10, 1938 - the sequence may be read as a counterpart to the pop star gallery of the uomini famosi of the 20th century youth culture which as an image of their idols is again the counterpart of these anonymous children's portraits. Helnwein has not painted the stars in a way that would be in keeping with their cult status, nor did he photograph the children as we are used to looking at children. Doubtless inspired by their faces wearing white make-up - which also gives a special character to the act of representing them - the children emerge as whole and complete human beings whose only "defect" is that they are small.

This conception accords with a way of life that characterized European society until the 17th century. Prior to the invention of childhood as a control system which holds together the bourgeois nuclear family in the way of a moral institution, children were neither innocent nor needy, neither pampered nor maltreated, but instead "small people", albeit not of too great importance in a juvenile population where life was brief and tomorrow full of uncertainty. Instead of meeting with arrogance, egocentricity and ignorance, however, they encountered friendliness, role models and challenges which made them capable of autonomous, actively relevant decisions already at an early age - as many sources prove. The precondition for this was a social milieu which the family offered economic and social but not moral support. Such secular feelings, however, contradicted both the salvation pedagogy of the church and the reason of state.

In the spate of images painted during the late Middle Ages and in early modern times, for the first time a distinction in the depiction of the child was made between the naked and the clothed one, the ideal type (as putto) and the individual child (in the grave portrait). In devotional images of the Madonna with child, Jesus was more and more frequently depicted realistically as a baby, in some instances - e.g. Mategna's work or the Wurzach altar by Hans Multscher - even shown wrapped in swaddling clothes as was in fact the custom for a long time in order to ensure the straightness of the baby's limbs. If we examine 15th century devotional images of the Madonna we note that alongside mere prettiness there is also a striking diversity of the child's expression that is not at all "childlike", sometimes even allowing Jesus to cast covetous or reserved glances at the viewer.

With an instinctive certainty of mind and hand Helnwein has responded with the concept of KINDSKOPF to the challenge of creating an exhibition in the early Gothic church of the Grey Friars at Krems/Stein that was secularized about 200 years ago by Emperor Joseph II. Helnwein uses the first opportunity for such a presentation in his native Austria and his home province of Lower Austria not only to sum up all of his previous work on the essentially autobiographical theme of the child in the surprising and very personal gesture of including his own children in the exhibition not as objects but as co-workers, but with his painting "KINDSKOPF" he also reacts specifically to the place of the exhibition and its traditional aura.

On the spot where in the medieval church the rood screen once separated the monks' choir from the laymen's nave and probably only a monumental crucifix symbolically marked the place of the sacred occurrence of offertory and transsubstantiation, the painterly transformation of Helnwein's creative concept of "The Night of Ninth November" ("Neunter November Nacht") evokes an immediate subjective emotion in the viewer that owes its power to a spiritual sublimation of the factual, similar to the effect of a devotional picture. It reflects the entire collective subconscious and Helnwein makes us aware of it by means of a joke - for in colloquial German, which only from the 17th century onward, the word "kindskopf" may refer to all sorts of childishness but certainly not to this contemplative fragile face.

This staging alone would contradict Helnwein's concept of a postauratic art that produces original paintings only as a "noble byproduct", if the artist did not disturb the mood set by the place by means of the children's works mounted in the nave. Allowing the original creativity and the power of the child's expressiveness to speak, is only one aspect of looking at these pictures and a secondary one at that, for without doubt, Ali Elvis, Amadeus and Mercedes Helnwein, who co-operated in the exhibition, are children who have received extraordinarily many stimuli through much attention and praise and who therefore have an unusual capability to express themselves. What is essential is how these children, especially the main contributer, Ali Helnwein, are learning not playfully but rather through a completely serious activity. Ali leaves the viewer in no doubt that he not only feels himself to be an equal partner of Gottfried Helnwein - but really is!

The hoopla which is stirred up by the interest in a matter can damage the latter's reputation, thus interfering with its intended effect. This is what happened to the epoch-making book Centuries of Childhood by Philippe Aries (to which I owe important ideas), and the same can be observed again and again in the reception of Gottfried Helnwein's work. The seemingly childish artist who again and again plays with poses, idols and fetishes, as most recently on the invitation and poster for the present exhibition; the not at all childish face of a (genuine) child; the creative achievements of children that have nothing childish about them: with this intertwining Helnwein succeeded not only in a decisive step in the integration of art with everyday life that has always been a goal of his - and anyone who has seen him live and work with his children will not doubt this even for an instant. The longing to abolish the dialectics of childhood and old age, of wishful thinking and reality in one's own life also hints at something utopian in the intertwining complexity of KINDSKOPF. "Painting is defending oneself" (G. Helnwein) - but is it defending oneself against reality or against the longing for that which is "underneath all thinking"?

Gottfried Helnwein, , 26. May - 7. July 1991

1991 Catalog, Museum of lower Austria Peter Zawrel

http://www.gottfried-helnwein-child.com

http://kristallnacht.helnwein.com