The Irish Times – August 20, 2001

AT THE KILKENNY ART FESTIVAL, 2001

AIDAN DUNNE, This year's Kilkenny Arts Festival helped take challenging work out of the gallery and onto the streets.

The point of the images is that they put it up to you as a viewer. Given that, one potential line of criticism is that they are designed solely to be provocative, like Marcus Harvey's portrait of Myra Hindley. But the abiding strength of Helnwein's work is that provocation is a means rather than an end; it is - however uncomfortable - morally grounded, if not necessarily in a way that will please all observers.

Nowhere is this more so than in Limerick, where EV+A pioneered the trend and which boasts, incidentally, in the form of the extension to Limerick City Gallery of Art, the nearest thing to a gallery that is actually a white cube.

The escape from the white cube had been a recurrent theme of group exhibitions in Ireland over the best part of the past decade. That is to say, getting art out of the privileged space of the gallery and into the real world.

A large part of the argument for strategy is that it makes it more likely that the art, and the artist, will engage directly with an audience composed of more than the usual suspects.

The policy had been applied in an almost ruthless way to the annual Claremorris Open Exhibition (coming up on September 15th), with mixed results.

The visual-arts strand of the Kilkenny Arts Festival had played its part in the trend in recent years. Sadly in this regard, the complimentary Sculpture At Kells didn't happen this year, apparently because of the foot-and-mouth crisis.

But in Kilkenny itself, Gottfried Helnwein, the Tipperary-resident Austrian artist, has taken to the streets in a big way. His photorealist images are much happier dispersed around the town and in the castle courtyard than they are penned up in Butler House, where their upfront directness and aspirations to cinematic scale sit a little uneasily.

Helnwein is famously confrontational, and his bold conflations of Nazi and Christian iconography, in Epiphany and other prominently displayed pictures, predictably generated some friction. Yet, in a way, one shouldn't rush to condemn condemnations of, or expressions or resignation about, Helnwein's work, no matter how superficial or uninformed they turn out to be. Because, let's face it, a large part of its effectiveness had to do with its calculated, barbed ambiguity.

The point of the images is that they put it up to you as a viewer. Given that, one potential line of criticism is that they are designed solely to be provocative, like Marcus Harvey's portrait of Myra Hindley. But the abiding strength of Helnwein's work is that provocation is a means rather than an end; it is - however uncomfortable - morally grounded, if not necessarily in a way that will please all observers.

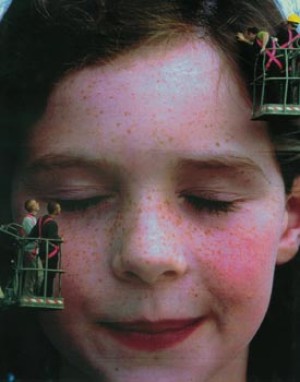

His beautiful photographs of Kilkenny children are, collectively, a recognisable derivative of his work Selection, which implicitly placed the viewer in the position of someone marking children for extermination. Strong stuff.

If that seems irrelevant in an Irish context, one could always point to Northern Ireland and to the scandals that have shaken the complacent authority of church and state in recent years.

What is more innocent, more open, more charming than the face of a child? Except that we are more than ever uncomfortably aware that the act of looking is not at all innocent, and Helnwein's children, with their closed, downcast eyes, decline to meet our collective gaze. Why? Perhaps because they insist on remaining within the orbits of their imaginations.

There is also, however, a slight unease arising from the uniformity of the images and the awareness that the subjects are being directed. Helnwein has a knack for throwing responsibility for what we are looking at back onto us, the viewers.