ART newsroom.com Joanna Hayman-Bolt – December 6, 2000

one-man show at Robert Sandelson Gallery, London, 2000

HELNWEIN

Any artist who sites Donald Duck and Jesus Christ as the most important influences in their art must be worth taking a look at.

In the row of pristine gallery fronts in London's Cork street, you cannot miss Gottfried Helnwein's show; it's the one with the gigantic Mickey Mouse staring out at you.

The Robert Sandelson Gallery has given us a stunning show of the infamous, Austrian born artist's recent work. Helnwein is on a mission to find the answers to questions that no-one in Austria would give him; such as why the post-war republic portrayed itself as a victim rather than as one of the first main perpetrators of Nazism.

It's rare to see such explicit confrontation with major social issues. References in art to such horrors as the two world wars and the Holocaust are usually made indirectly through symbolism or abstraction. Despite attention given to the users of shock tactics, the majority of contemporary artists shy away from figurative images which directly illustrate horrific social realities, preferring instead to use personal concerns or the heavy use of irony. This is where Helnwein differs. His photo realist paintings are strongly illustrative of the results (rather than the acts) of Nazi oppression in the Second World War.

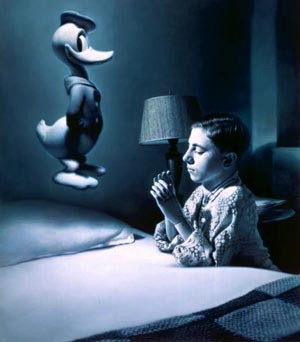

Where do Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse come into all this? Helnwein uses the strategy, known to many film makers, of juxtaposition; take a serious "adult" phenomenon such as death or sex and place it together with a picture of childlike innocence and the mental disturbance to the viewer is increased ten fold. The use of children and cartoon characters have several functions. They are not just a filmic special effect, although the paintings are particularly uncomfortable to look at for this reason; they have particular relevance to the artist both in terms of his own experiences and his concerns with some of the muffled truths of the Second World War.

Helnwein was born in Austria; a country that had willingly embraced Nazi Germany. For decades after it's defeat the Austrian population had great difficulty in coming to terms with the evil association. Helnwein felt that for this reason he had been brought up in a dysfunctional society.

The artist wrote of this time: "My childhood was a horror. Born right after the war, I lived in a world of deep depression and unlimited boredom . . . I never saw anyone laughing and I never heard anybody sing. I always felt I have (sic.) landed in limbo. A two-dimensional world without colours. My real life began when I got my first Mickey Mouse comic book from the Americans - when I opened a world full of three dimensions and wonders . . ."

The Mickey Mouse that stars in Cork street ("Mickey Mouse", 1995) is far from colourful. Painted in tones of black and white, although his radar ears and doorknob nose is as sweetly comical as ever, his smile is menacingly sinister. The sheer size of the famous mouse becomes threatening and we begin to see the character through the eyes of a terrified child in war time cinema. Helnwein explained that he began to paint as a way of diffusing his frustration with not having his questions about the war answered. An early picture of his was a portrait of Adolph Hitler painted with his own blood from self-inflicted razor cuts to the palms of his hands. Having painted Hitler portraits throughout the 1970's he began to attract attentions. Ironically some of it came from Neo-Nazis knocking on his door to see the freshly painted portraits of the "Fuhrer". Another irony is the fact that Helnwein studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna - as indeed did Hitler.

Power is given to Helnwein's confrontations on canvas by virtue of him being an extremely skilled painter. His photo realism is immaculate and highly effective. Even under close scrutiny, the subtle shades and invisible brushwork makes it hard to distinguish the painting from a photograph. This hyper-realism is impressive not because "it looks like a photograph" for that would cancel out the purpose of painting. It is impressive because this controlled application of paint is cool enough to create an air of photo documentation without being sterile. Helnwein creates a "photo-montage" in paint, blending his own images with genuine W.W. II photographs. The result is subtly disturbing. The atmosphere in all the paintings is slightly dreamlike and the characters appear in these dramas like spectres. "Epiphany I (Adoration of the Magi)", 1996, is a dark and brooding image of five S.S. officers gathered round a modern day Aryan goddess as the Madonna who holds a naked baby "Jesus", his black hair swept across his brow in the style of Hitler. The image is huge (2 meters by 3 meters) and of a cinematic wide screen format. It's easy to see why Helnwein has been at the centre of several small controversies. The sacrilegious nature of the painting upset not only the orthodox Christians but ironically those associated with the officers depicted. Helnwein is being sued by the widow of one of the Nazi officers depicted for the unauthorized use of the image of her husband. A bit rich, seeing as her late husband cannot have had one of the clearest of consciences in political history.

Helnwein exploits the image of the child in a Balthus-type manner. Photographs of early pubescent children are used in a similar way to a hard hitting Lewis Carroll. In another large scale painting, "Epiphany III (Presentation at the Temple)", 1998, a young girl dressed in white lies prone, unconscious or perhaps dead on a table while a group of nine disfigured war veterans stand around in sombre witness. The painting reminded one of Rembrandt's "Anatomy lesson of Professor Tulp", 1632, and the similarities go beyond the compositional. The image is painfully tender, the light that glows around the young girl - apart from making her angelic - reflects the revelations of the medical experimentations on children during the war years. The theme of the child was spurred by an interview in an Austrian tabloid in which the country's Head of Psychiatry, Dr. Heinrich Gross, admitted killing children at Vienna's Am Spiegelgrund Paedriatric Unit during the war by poisoning their food. Helnwein painted "Life Not Worth Living" - a water colour of a little girl "asleep" with her head in her plate; it initiated a nation-wide debate which ultimately led to a court hearing and Gross' resignation.

Upsetting as these images are - it is the foetal heads that tower 4 meters above the viewer on entering the gallery that start the provocative ball rolling. Helnwein makes giant portraits of these pre-natal babies in the three canvases "Angel Sleeping I, II and III", 1999. The ghostly images (manipulated photographs) have the merest hint of painted colour casting a blue and yellow wash over the "angels". In this way Helnwein captures that uncanny hue that characterizes foetuses floating in a stillborn liquid from which they will never emerge. Unlike Damian Hirst's sharks and livestock in formaldehyde that made the headlines just a few years earlier, Helnwein allows us no intellectual distance. The face that is the beginning of a human being confronts a wide range of issues; not all of which would be wholly negative. However, in the context of this experimentation during the war - the face reveals more tragic truths of vile inhumanity in the 20th century.

It's easy now for an artist to shock with their creations and visions and many seek sensation this way. But Helnwein creates sensation for the viewer as much as he has for the Austrian and German newspapers (a more recent controversy that hit the papers resulted in he and his family moving to Ireland in 1997). His sensitivity comes through a careful use of tender images and technical sophistication. The images don't hit you, they absorb you and let you go away sharing some of the artist's disgust at human kind. It's a brave and difficult job to deal with such issues without being sensationalist or just an illustrator of horror. Helnwein reaches the limits of the blood thirsty and it would be easy to place him in the long line of German and Austrian artists from Grunewalde to Otto Dix who were uncompromising in their portrayal of human torture and butchery. Indeed, Helnwein's most effective works are those which refrain from direct illustration of physical suffering. The fact that he makes Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck so haunting somehow makes a greater impression than blood and bandages. In this way the artist makes a universal statement about the importance of a child's innocence and happiness, without which there can be little hope for the sanity of future generations.

Gottfried Helnwein, one-man show at Robert Sandelson Gallery, London, 2000

06.Dec.2000 ART newsroom.com Joanna Hayman-Bolt

The Art of Gottfried Helnwein and the Comic Culture:

Gottfried Helnwein at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2000

www.helnweincomic.homestead.com/

http://www.gottfried-helnwein-interview.com/